Anjette Lyles, Restaurateur of Death

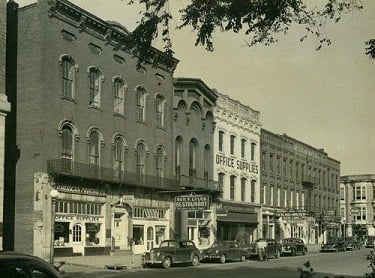

One of the most popular lunch spots in 1950s Macon was Anjette’s on Mulberry Street. With a handy location for a lot of local offices, most weekdays it was packed with white collar workers. Businessmen and lawyers, taking a break for some fine Southern food and hospitality. Though the main draw of the place for the mostly male customers was the owner, Anjette Lyles. The young widow had a friendly manner that instantly put her customers at their ease, and she’d often just sit and chat with them while they ate their lunches – and, of course, one of her famous desserts. Sure, she might dress a little too flashily and drive a fancy car, but it was probably just jealousy that had the local gossips labeling her as a “fast woman”. Little did they know the secrets Anjette held; but they’d find out soon enough what sort of a woman she really was.

She had been born as Anjette Donovan in 1925, the only daughter (though she had two brothers) of a reasonably well off couple. Anjette was well educated, though she was a mediocre student. Her fellow students mostly remembered her as a girl who usually got what she wanted, through charm and manipulation, but who remained well liked regardless. In 1947 she married Ben Lyles, a young man who (like most young men at the time) had fought in the Army during World War 2. After their first daughter, Marcia, was born in 1948 Anjette went to work at the Lyles family restaurant alongside Ben’s mother Julia. (His father had passed away years earlier.) She turned out to have a real talent for the business, and proved a hit with the clientele. And her daughter, baby Marcia, was the darling of the restaurant staff.

Though Anjette’s professional life was going well, her home life was far from ideal. Ben hadn’t had a good war – he’d picked up a throat infection that turned into rheumatic fever and left him unable to work and frequently in pain. This did entitle him to a veteran’s pension, but it also made made him irritable and drove him to drinking. Ben also picked up a gambling habit, and it might have been debts from this that led him to sell the family restaurant in 1951 for the ridiculously low price of $2,500. Anjette, who had just given birth to their second daughter (named Carla), was furious that he hadn’t consulted with her before doing this. The pair argued bitterly over it, and the arguments only got worse when the Veteran’s Administration decided to cut Ben’s pension to a tenth of what it was as they’d decided he was now fit to work.

As if to prove the VA wrong, in December of 1951 Ben Lyles fell ill. The doctors were confused. It wasn’t a recurrence of his rheumatic fever, and in fact they weren’t quite sure what it was that was wrong with him. He had nosebleeds and convulsions, and had to be hospitalised. When he went into a coma in January the doctors decided it was encephalitis, but by then it was too late for effective treatment. He never regained consciousness and died on the 25th of January.

With Ben’s death Anjette was forced to move out of the small apartment they’d shared and back into her parents’ house. She got a job working in a new restaurant, and spent the next few years learning the trade while saving every penny she could. [1] She had a single goal in mind, and Anjette always got what Anjette wanted. Finally, in April 1955, she bought back the Lyles family restaurant for $12,000 – nearly five times what Ben had sold it for. Understandably she felt that entitled her to change the name. So she reopened it for business as “Anjette’s”.

Anjette had clearly learned a lot from her time working in other restaurants, as “Anjette’s” was soon even more popular than “Lyles” had been. She hired her mother-in-law Julia back to give the place some continuity, as well as other staff, but it was Anjette who was the face of the new restaurant. There was an airport nearby, and the place immediately became popular with the pilots as well. One of them was Joe Neal Gabbert, who everyone called Buddy. Buddy and Anjette hit it off and started seeing each other shortly after she opened the restaurant, and in June of 1955 they went off on holiday to Texas and New Mexico together. It was a surprise to everyone when they returned with the news that they had decided to get married while they were away.

Anjette’s new marriage seemed to be happier than her last, even though she was still living at her parents’ house. It may have helped that Buddy’s job as a pilot both meant that he couldn’t become a drinker and that he was frequently away. Some of the local gossips made a lot of this, claiming that Anjette was having affairs. Most found plenty of fodder in Anjette’s fascination with magic and similar practices, considered vaguely scandalous in the highly religious southern USA. Mostly this took the form of her dragging her friends and relatives along to see fortunetellers at fairs, but on occasion her staff told stories of finding her in the restaurant lighting coloured candles and whispering to them when she thought nobody was around.

In October of 1955 Buddy went into hospital for a minor operation on his wrist. At first it seemed to go well, but shortly after returning home he developed a skin rash and a fever. The fever got worse, while the rash spread all over his body. He was soon back in the hospital but the doctors were baffled by his condition and couldn’t find a cure. He died on the 2nd of December, leaving Anjette a widow all over again. The doctors hoped an autopsy might tell them more about why Buddy died but Anjette refused to grant permission, telling them that Buddy wouldn’t have wanted to be cut up after his death.

Anjette’s behaviour after Buddy’s death raised more than a few eyebrows, as within a few months she had not only legally changed her name back from Gabbert to Lyles but had also started dating another dashing young pilot. Because of his job Buddy had a fairly hefty life insurance policy, and when that paid out Anjette bought a house for her and her girls. She also bought herself a fancy car, which didn’t go down well with the respectable ladies of Macon. But then Anjette never really had time for them either.

Julia Lyles moved into Anjette’s house as well, where she would take care of her grandchildren while Anjette was working at the restaurant. Relations between the two women were strained, especially around the issue of the elder Mrs Lyles refusing to make a will. Perhaps she didn’t want to confront her own mortality. However she did have a surviving son named Joseph, and Anjette was clearly worried that if she died intestate then Joseph would inherit it all. This became an immediate concern in 1957 when Julia became ill. For a while it seemed just a summer chill, but then she began vomiting blood and had to be hospitalised. Anjette was a frequent visitor, bringing her food from the restaurant, but she was pessimistic about the old lady’s chances. She soon proved to be right when Julia died on the 29th of September.

Shortly after Julia’s death Anjette produced a will that she had finally persuaded her mother-in-law to sign. It left a third of her estate to Joseph, a third to Anjette and the remaining third to be held in trust for her two grand-daughters. It turned out that Julia had almost $11,000 in savings, so this was a reasonable amount (though some were surprised that it wasn’t much more). That might explain why Anjette didn’t seem very upset about the death, at least in the eyes of the judgmental Maconites.

They might have been unfair though, as Anjette did seem somewhat troubled to those close to her. This took the form of aggression towards her nine year old daughter Marcia, who Anjette somewhat curiously called “a Lyles-looking son of a bitch”. On several occasions she even threatened to kill the child, though her younger daughter Carla was usually able to calm her down. All the stress seemed to have an effect on young Marcia, though, and in March of 1958 she started coughing in the restaurant and complaining of a headache. Anjette gave her the traditional country remedy for a fussy child; a spoonful of sugar with whiskey poured over it. But that just seemed to make things worse, as Marcia started vomiting and Anjette had to take her home. A few days later Anjette was hospitalised. In an ill omen, the small local hospital put her in the same room as her father, step-father and grandmother had all occupied before they died.

Perhaps because of this, Anjette seemed convinced that Marcia was going to die. She brought the child fruit drinks and tea in the hospital, but they didn’t seem to help. In fact, they only seemed to make it worse. It was around now that people began to get very suspicious of Anjette Lyles. After a couple of weeks Anjette began making funeral arrangements for her daughter, though this was immediately followed by a sudden improvement in Marcia’s condition. It didn’t last though, and soon she was sick again. For some reason the doctors couldn’t fathom, her kidneys seemed to be failing. The condition was accompanied by hallucinations, and the poor child would beg to be protected from “beasts coming after her, insects attacking her, and of worms crawling out of her fingers”. Most found this very distressing, and thought it very inappropriate when Anjette laughed at it. Her excuse was that nervous laughter was how she reacted to things disturbing her so much.

Marcia died on the 5th April, with a stony-faced Anjette by her bedside. She was autopsied after her death, but the coroner could not find any obvious cause for her kidneys failing. A few days later he received an anonymous letter, which later turned out to be sent by one of the employees at Anjette’s restaurant. She had been speaking to Anjette’s maid who had mentioned Anjette keeping ant poison in the house, allegedly to deal with an infestation at the restaurant. Since the employee knew that there was no such infestation, that had combined with their misgivings about Anjette’s behaviour to make them decide to write to the coroner. When he purchased a bottle of the same ant poison he noticed that it contained arsenic, and he thought that arsenic poisoning might have caused the symptoms he had seen. He sent the bottle of poison along with samples of Marcia’s hair and kidneys off to the state laboratory for investigation, and gave Anjette a call.

The coroner told Anjette that he was worried that Marcia might have accidentally drunk poison. Anjette came in to see him, with a bottle of the ant poison and her younger daughter Carla in tow. Carla told the doctor a story about her, Marcia and two other children playing “doctor” and dosing Marcia with the “medicine”. The doctor was unconvinced, but told Anjette that she should warn the mother of the other two children. So Anjette looked up a name in the phonebook, called a number, and told the person on the other end their children might have come into contact with poison. (Later, the mother of the two girls would say that she had received no such call, and that her name wasn’t even listed in the phonebook.)

Anjette herself was hospitalised for an inflamed varicose vein a month after Marcia’s death, and it was while she was in hospital that the authorities decided to arrest her. She was unable to walk and was in a wheelchair when she was arraigned on four counts of murder, for both of her husbands and Julia Lyles as well as Marcia. She was only indicted for trial for the murder of Marcia, but the arraignment allowed the prosecution to bring in evidence related to the other three deaths as evidence of “system”.

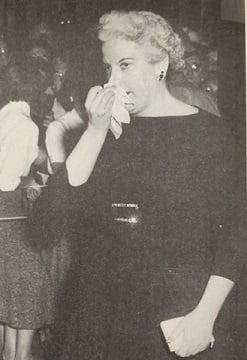

Naturally, the arrest of Anjette Lyles was an immediate sensation in both Macon and across the state. The newspapers drove themselves into a frenzy over the “glamorous, platinum-haired widow”. As if the murder of her family weren’t enough, the discovery of her books on voodoo and magic and the related paraphernalia by the police (and the stories of her whispering to candles) gave the stories an irresistible hook. As a result a huge crowd turned up to watch the opening of Anjette’s trial in October of 1958.

Arsenic is a metallic element, which is one of the huge pitfalls in using it to poison – it can be found in the corpses of its victims long after their death. Julia, Buddy and Ben had all been exhumed and all three had been shown to contain arsenic, as had the samples from Marcia’s autopsy. To counter the objection that this could have been introduced in the embalming process, the prosecutor even brought in the local undertaker to testify that his fluids didn’t contain arsenic. A re-examination of their symptoms by the medical expert witnesses all added strong evidence of “system” to the already strong evidence in Marcia’s case.

Anjette’s defence against this hinged around a letter purportedly written by Julia claiming to have poisoned the other two and then poisoned herself out of guilt. However the maid who was supposed to have claimed to have found this letter in the old lady’s purse instead testified for the prosecution, claiming Anjette had tried to make her go along with the story. Analysis of the letter showed it to be a forgery, and even more seriously the same analysts concluded that the same person had forged Julia’s signature on the will that Anjette had supposedly persuaded her to sign.

With that evidence undercut so severely, Anjette’s defence mostly just consisted of her denying the allegations against her. She said that Ben had drank himself to death and that Buddy’s rash had been around before they were married, though she had no real evidence to back this up. As a result it’s not surprising that the jury only took an hour to declare her guilty and recommended against mercy. Anjette was sentenced to die in the electric chair for the murder of her daughter Marcia.

Naturally Anjette appealed the sentence, but her appeals failed. She was put onto death row at Reidsville State Prison, but her sentence was postponed when Governor Ernest Vandiver granted her a stay of execution. Anjette would have been the first white woman executed in Georgia’s history, and some people were unwilling to cross that line. (They’d been much less reluctant thirteen years earlier when Lena Baker killed a man. He had been holding her as a sex slave, and she killed him in self defense when he tried to murder her. But of course Lena was black, and the man she killed was white, and that was all that mattered to them.)

Governor Vandiver appointed a sanity commission to examine Anjette, and they decided that Anjette was schizophrenic. This meant that she could not be executed, and so she was transferred to the Central State Hospital, better known as Milledgeville mental hospital. There she would stay for the next 18 years. She became well known to the other inmates for telling fortunes with playing cards. Despite the improvements in psychotropic treatment over that time, she was never considered “cured”, and in fact she told one friend that she’d never let herself be declared sane for fear she’d then suffer the consequences of the the crimes she’d committed. She died in 1977 of a heart attack, aged 52 years old.

Given the publicity that had surrounded her trial, Anjette’s death attracted surprisingly little interest. In a somewhat morbid twist, Anjette wasn’t buried on the grounds of the asylum like so many who died there. Instead her remains were buried in the Donovan family plot in Wadley. In the same plot were the bones of her daughter Marcia and her first husband Ben, two of the people she’d been responsible for ending the lives of. Death, the great equaliser, had brought them all to the same place in the end.

Images via Murderpedia except where stated.

[1] Several sources claim she got a large life insurance payout for Ben, but given his rheumatic fever it’s unlikely he would even have been able to get insured. If she did get some money, it wasn’t enough for what she had in mind.

I remember taking a field trip planned by a psychiatry professor at Macon Junior College around 1976 to Milledgeville ,GA to visit female inmates at Central State Hospital. You can only imagine who me and my classmates met there ! The infamous murderer Annette Lyles. She was the cook for the ward of criminally insane women!

Great read, thanks!