Lola Montez, the Spider Woman – Part 1

In the 19th century, there were few women as notorious as Lola Montez. The exotic beauty wowed the courts of Europe, and counted both famous composers and rulers of nations among her conquests. With her famous “Spider Dance”, she mesmerised crowds, producing as much outrage at her raw sensuality as she did adulation. But this controversial figure did not come from Spain, the daughter of a matador, as she often claimed. Nor was she the illegitimate daughter of Lord Byron, as one story had it. Instead, she was born as plain old Eliza Gilbert in the shadow of Ben Bulben in Ireland, and the same name would be on her grave. But in between, Lola was whoever she wanted to be.

Lola’s father was an English soldier named Edward Gilbert, on tour in Munster to police the troubled province. Her mother was Eliza Oliver, the illegitimate (but acknowledged) daughter of Charles Oliver, who had been high sheriff of Cork and an MP in his day. The two were married in 1820, and a year later (after Edward’s duties had taken him north to county Sligo) they had a daughter, named Eliza after her mother.[1] The following year, Edward arranged rotation out of his unit, changing places with a new cadet who was heading out to India. It was a big step, but it promised both increased pay and increased excitement. So the young family set out, but tragedy was waiting en route. At some point during the long journey, Edward contracted cholera, and by the time they arrived in Dinapore where he had been posted, the disease was in its final stages. By the date he had been due to report for duty, he was dead.

The widow Eliza moved to Calcutta and considered her options. The only real viable one was remarriage. Fortunately, she was an attractive 19 year old with a pleasant manner, and it was not difficult for her to find an officer willing to take that step. Lieutenant Patrick Craigie, from Montrose in Scotland, was the lucky man. By all reports he was as fond of Lola as if she was his own daughter, but the headstrong young girl was a handful – throwing tantrums and resisting all attempts to discipline her. It was decided to send her back to Scotland, in the hopes that Craigie’s father, a chemist who had raised nine children, would have better luck. But it was not to be. The celebrity of being “the strange Indian girl” had a stronger effect on Lola than anything else, and she must have wearied her grandfather greatly. Four years later when his daughter Catherine moved to Durham to set up a boarding school, Lola was one of the first pupils enrolled in it. A year later, her father (by now a Captain) had her put in an exclusive ladies school, the Aldridge Academy in Bath. Here, French was treated as a first language and this enforced multilinguality would serve Lola well in the years to come. It was also here that the foundations of her dancing career were laid, though the stern women who ran the academy would have had little inkling of what use their instruction would be put to.

In 1837, at the age of 16, rather than consent to the marriage her mother had arranged for her Lola eloped with a visiting officer, a friend of her stepfather, named Thomas James. The marriage devastated her mother and outraged the Craigies (who had never really approved of Patrick’s marriage). Her marriage with Thomas was profoundly unhappy, however. When he was reposted to India she accompanied him, returning for the first time in over a decade to her childhood home. There she left him (possibly due to his physical abuse for her “willfulness”), and though her mother persuaded the two to reconcile it was not to last. On a trip back to London Lola was blatantly unfaithful with another passenger, a Lieutenant named Lennox, and back in England the two continued their affair. Eventually this led to her husband seeking and receiving a divorce (with no permission of remarriage for either party) [2], and to Lola being disowned by her stepfather’s family. Lola was branded an adulteress, a great shame in Victorian society. The elite stratum she had moved among was now forever closed to her. Her mother even took to wearing mourning in memory of the daughter she considered dead. In desperation she fell back on the dancing she had loved in her childhood. At the age of 21, in 1842, Eliza James abandoned the names she had inherited from a father she did not remember and a husband she despised, and took to the stage as Lola Montez.

At that time, the life of a stage performer embodied the hypocrisy of Victorian society. Ballet dancers, for example, were paid less than a living wage, as the expectation was that they would use their exposure to gain a lover from among the upper class who would sustain them. Here it was, then, that Lola would find herself bartering her sexual favours for power and influence. Her first appearance, in London, was initially a success, and her performance finished to thunderous applause and rave reviews in the papers. Unfortunately for Lola, some gentlemen in the crowd recognised her as the notorious adulteress Eliza James, while others recognized her “Spanish” dancing as a fraudulent imitation. Though she vigorously defended herself in letters to editors, she was forced to decamp to Paris. The controversy had the effect of amplifying her fame, however, and she snared at least one highly born admirer – Prince Heinrich of Leipzig. He took her as a mistress, and when she proved to be a touch too lively for his taste, he got rid of her by arranging a series of appearances in Dresden, which soon led to an engagement in Berlin. There she met with a mixed reception – her sensuality won over the crowd, but her lack of technique and variety offended the critics. Here again, her knack for catching the eyes of the rich and famous served her well, and she wound up dancing at a reception that Frederick William IV of Prussia was holding for the Czar of Russia. A quick rise, for a woman with a dancing career of, at the time, less than three month’s duration.

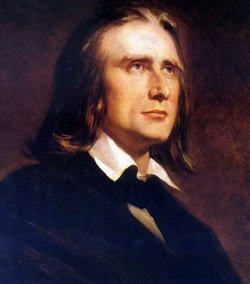

In 1843 she moved to Warsaw, which at the time was ruled by the same Czar she had danced for in Berlin, and it was here that she first began to be involved in radical politics. The manager of the theatre, Colonel Ignacy Abramowicz, was somewhat alarmed by this as he was also the city’s chief of police. He arranged for the audience at one of her performances to be seeded with his stooges, who would boo and hiss her – but in the event, this only provoked her supporters to greater acclaim, and a riot threatened to break out. Lola, with her usual flair for the dramatic, took the opportunity to denounce the Colonel, declaring that his outrage came from her refusal to “submit to his infamous proposals”. Lola became a rallying point for resistance against the Russian occupation, and the regime expelled her from Poland. With word of her rabble-rousing tendencies going ahead of her, she received a chilly welcome in St Petersburg, and only made a single appearance on stage before having to move on. This left her aimless, and it is at this time that she is said to have read a newspaper article about the composer Franz Liszt, who was touring Europe to great acclaim at the time. Here, she decided, was her key to further stage success.

Liszt was, at the time, the most popular musician in Europe, but Lola had little difficulty arranging first a meeting, and then a relationship. She travelled around Dresden with him, meeting Wagner (who disliked her intensely), and introducing Hans von Bulow, a young man who had helped her fend off an overzealous fan in Berlin, to the conducter he idolised. [3] The relationship soon soured, however, as Lola tired of playing second fiddle to the “great man”, and began creating great histrionic displays to get attention. One story had it that Liszt, tiring of her, sneaked out while she slept to avoid the inevitable fiery tantrum his leaving would provoke. Regardless of how the relationship ended, however, when Lola left Dresden she headed for Paris with a full set of introductory letters from Liszt. For a long time, she had declared her intention to conquer Paris, and now she had been given the keys to its gate. The name of Liszt and her own charm soon gained her a following, and pressure soon mounted for her to be allowed to take the stage of the prestigious Paris Opera to dance El Oleana – one of the few dances she actually knew. Unfortunately, however, the Parisian audience knew dancing when they saw it, and Lola’s lack of skill and experience (at this stage she had been dancing for less than a year) stood out like a sore thumb. She made two appearances, but was not invited for a third. Even her fraudulent Spanish origin was soon penetrated, though this fact did not really make much of a dent in her popularity. Instead she settled into the bohemian side of Paris society, becoming friends with Alexandre Dumas among others, and gaining notoriety for displaying a surprising talent for pistol shooting. Dumas would say of Lola, “she is fatal to any man who dares to love her”. Unfortunately for Lola, this was soon to prove true.

Alexandre Henri Dujarier was the editor of La Presse, one of the first mass market newspapers in France. He had seen Lola dance, and regardless of the merits of the dancing he had fallen desperately in love with the dancer. He managed to get backstage and introduce himself, and it was through his influence that Lola found her entry into the bohemian class that she grew to love. Here she found a spiritual home, and when Dujarier proposed marriage, she accepted. The terms of her divorce with Henry James made this bigamy, but it’s doubtful if Lola even considered that aspect of the affair. It was to turn out to be an academic issue, as the marriage never took place. Dujarier attended a party at the Palais Royal. He had asked Lola to stay home as he thought it would be a rough crowd, but a friend had invited him and he thought it would be rude to refuse. While there he got into an argument over a card game with Jean-Baptiste de Beauvallon, a journalist from a rival newspaper. The argument escalated to the point where Dujarier challenged the other man to a duel. The next morning, he regretted his rashness, but his honour refused to let him back down, and the duel went ahead. Dujarier fired first and missed, then dropped his pistol and accepted his fate. His opponent, a more practised shot, took careful aim and fired. Dujarier was killed, and Lola’s heart was broken.

At first Lola stayed in Paris, but as with the rest of her “set”, she left the city during the summer. She headed to Bonn, which was hosting a great music festival in honour of the late Beethoven’s seventy-fifth birthday, organised by her old friend Liszt, and then moved on around Europe, sparking scandal wherever she went. Finally she returned to Paris, but the acquittal of Dujarier’s killer the following spring seems to have soured her on the city. [4] She resumed travelling around Europe, where she numbered among her conquests Robert Peel, son of the former English Prime Minister of the same name. Finally she decided to go back onto the stage. While travelling to Vienna, she passed through Munich, the capital of Bavaria, and secured an engagement to dance on stage in the Royal Theatre during the intervals. A former acquaintance secured her a private appointment with the King, Ludwig I, and the two immediately hit it off. [5] The King was a fan of both beautiful woman and of all things Spanish, and Lola entranced him – even more so once he had seen her dance. The public response was, as always, mixed to her performance, but there was no doubt that Ludwig was smitten. The sixty year old monarch even began composing love poems to her in Spanish. The relationship soon became official – as official as such things get, anyway – and Lola became the king’s mistress. The most famous role of her career had begun.

Continued in part 2. Images via wikimedia.

[1] Lola’s birth year is frequently (incorrectly) given as 1818, this was due to a lie she gave to get out of school which stuck beyond her ability to deny it. Even her tombstone has the wrong year and age on it.

[2] A divorce permitting remarriage required an Act of Parliament, which needed both political influence and a donation of £1000 to cover the costs. As always, it was one law for the rich and powerful, and another for the “normal” citizens of the realm.

[3] Hans would, inspired by Lizst, go on to become one of the greatest German conducters, along with being a composer in his own right.

[4] Even though murder through duelling was illegal, it was common for French courts to acquit duellists. In this case, however, since de Beauvallon had deliberately provoked Dujarier into the duel and then shot him while he was unarmed, public outrage was so great that he was actually retried the following October on the grounds that he had perjured himself in the first trial. He had claimed to have followed the duelling code, but the pistols used were actually his brother-in-law’s and had been used by him before, giving him an unfair advantage. He was sentenced to ten years for murder.

[5] A story at the time had it that Ludwig had asked Lola if she padded the bosom of her dress, and rather than reply she had simply cut it open with a pair of scissors to reveal her natural glory. The story fails to mention how she would have managed to return to her hotel (as she did) with her dress in that state, and so is probably false