Close Reading Mary Oliver

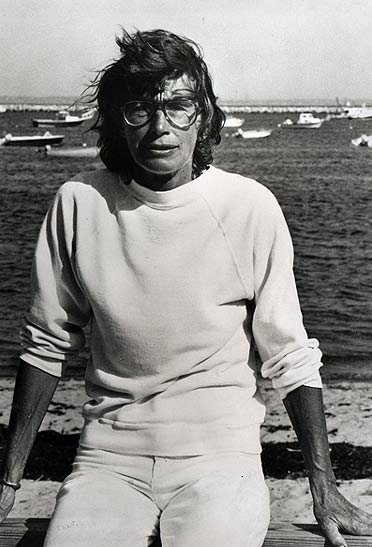

Mary Oliver was born in 1935, Ohio, America. She has published over a dozen collections of poetry and has been the recipient of numerous awards including the Pulitzer Prize. Her poetry is often a philosophical journey surrounded by nature. Maxine Kumin calls Oliver ‘A patroller of wetlands and an indefatigable guide to the natural world.’ Oliver is a keen walker, often pursuing inspiration on foot.inflatable game

This poem, just as the ‘wild geese’ are moving over the landscape, moves over us as an encapsulation of wisdom. Some critics have accused Oliver of being didactic, usually considered a bad thing in poetry, very few artists get away with dictating their beliefs through their art. But this poem, coming from the Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson tradition is an exception to this rule. She is speaking of beauty in nature and of a nature-consciousness, which we are all a part of. As a result, the poem not only gets away with it but also excels itself.

The voice rather than being holier-than-thou comes through like an elder of a tribe passing down wisdom, or a witch doctor – as if the words are being channelled from some higher source through the speaker. The tone is not severe like some damnable decree spoken by Jehovah; it is rhapsodic as the beauty it describes sweeps us along with the nature of the world.

The voice rather than being holier-than-thou comes through like an elder of a tribe passing down wisdom, or a witch doctor – as if the words are being channelled from some higher source through the speaker. The tone is not severe like some damnable decree spoken by Jehovah; it is rhapsodic as the beauty it describes sweeps us along with the nature of the world.

In fact, the wisdom it speaks of is the antithesis of all the major religions’ doctrines. While Judaism, Christianity and Islam all have major preoccupations with good and evil, ‘You do not have to be good’ suggests the opposite. The next sentence doesn’t beat about the burning bush either; it alludes to Jesus’ forty days and nights spent in solitude wandering through the Judean desert fasting. We are told we don’t have to go to such lengths, all you have to do is ‘let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.’ Again, historically we have been made to feel ashamed of our bodies, but here we are told to love them, to be natural and trust our instincts. ‘Soft animal’ suggests that we are not cut off from nature but a part of it. Animals do not go about doubting their place in the world so why should we?

The next line directly invites us to speak, this could appear at first to be like a priest at confession, ‘Tell me about despair, yours.’ Then straight away the power is given back ‘and I will tell you mine.’ The trials and tribulations we suffer are something we all experience, it is part of life, but no matter how much pain we go through ‘the world goes on.’ If we can take our imaginations away from ourselves for a moment, we can see that we are part of something greater.

The next lines take us through that, across a vast landscape of ‘mountains’, ‘trees’, ‘prairies’, ‘rivers’ – thus out of ourselves. Then we are taken up to see the ‘wild geese’ which brings us back up to the title. By taking us through nature this way and up to the geese flying over this moving landscape, we are not just invited to see the geese but have been shape-shifted to become them; to see the whole landscape. God is not dictating to us, we have become like gods ourselves, to have a godseye, or birdseye view of the world.

We are the ‘wild geese’ and all of nature. The geese are also ‘heading home again’. Home is where the heart is, a symbol of nurturing and love. God is love, remains the cornerstone of all religions.

All the way we are being empowered and lifted up by this mystic wind,

‘no matter how lonely/ the world offers itself to your imagination.’

These lines are similar to the sort of thing President Obama might say. If we open our minds we can achieve anything, like a new form of leadership, of people uniting and working together; people from all walks of life seeing themselves as one people,

‘announcing your place in the family of things.’

The world is here for us sustaining us like a mother, (mother earth) and ‘calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting.’ When Obama was elected, people spoke of a new age in politics, there was a seismic shift in peoples’ imaginations. It was ‘harsh and exciting.’

The rhetoric used in this poem with the opening refrain of ‘You do not have to’… and the repetition of ‘meanwhile’… is very similar to the pattern that a political speech might follow. Politicians are very aware of the persuasive power of words – just as poets are.

The form of the poem follows no particular system of rhyme or metre – this is called free verse. As with all good poems the form echoes the meaning, free verse perfectly complements what is being said. If this were written as a sonnet: following iambic pentameter, a set rhyme and other specific devices, it would have hindered the shape and upset the flow of the piece. The poem needs to find its own rhythm and rhymes as it swoops along; the line-breaks fall naturally rather than being manmade. The beats may not be regular in free verse, but like the ‘wild geese’ flying home that does not mean it doesn’t follow a pattern.

The stressed or long syllables like, ‘do not’, ‘be good’, ‘your knees’, ‘clean blue’, are what’s called spondee. These and the other long feet scattered throughout help give the expanse of the American landscape – and of course the ‘wild geese’ flying high in the ‘clean blue air’. This truly inspirational poem does a lot in a few words, reminding us no matter how lonely we feel inside, the world outside offers gifts. What’s more, as Einstein did – it believes in the imagination.

Mary Oliver’s new and selected poems is published by Bloodaxe books.