Out Here | 6 | A Dirt Clod Among Stars

I look out the Luan Gallery’s tall windows at the river Shannon. It moves westwards through Athlone like a slow, black brushstroke. Sunlight dances on the water, boats rock with its flow, swans glide downriver. I turn away and back to the gallery’s exhibition – a collection of landscapes titled Untitled [Landscape]. Curated by Dr. Louise Kelly and Davey Moor, these artists’ re-imaginings of our world’s lands jump from the gallery’s off-white walls. There are only two of us here. And the rooms are blessed with silence. A lessness that emphasises the pictures’ loud colours and compelling presences. So that they seem to fill all the senses, not just the eye.

Alison McCormick’s Full Moon, a shadowy etching of bare trees, smells of autumn air. Richard Mosse’s You Are Wherever Your Thoughts Are, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, is quiet as the dawning that colours the fields it depicts. A T-Rex steps out of the trees in Garry Loughlin’s Untitled, (Kentucky). A shock of scales and claws and teeth against the azure sky. While the orange and red hues of Soft Day by Fergus Smith are silken as fur. The Luan Gallery is small. Untitled [Landscape] consists of just thirty paintings in two rooms. But within this nest of creativity is a world of sensation. That illustrates the unique relationship between each human on Earth and their world.

There are as many worlds as there are perspectives. The poet-mystic William Blake wrote that “that call’d body is a portion of the Soul discern’d by the five senses, the chief inlets of Soul in this age.” He realised that through the senses we can reach the spirit, that what the body perceives the soul interprets. While the information interpreted may be the same from person to person, their interpretation of it will be individual. So a different, distinct cosmos resides within each human being. Each of them as vast and mysterious as the next.

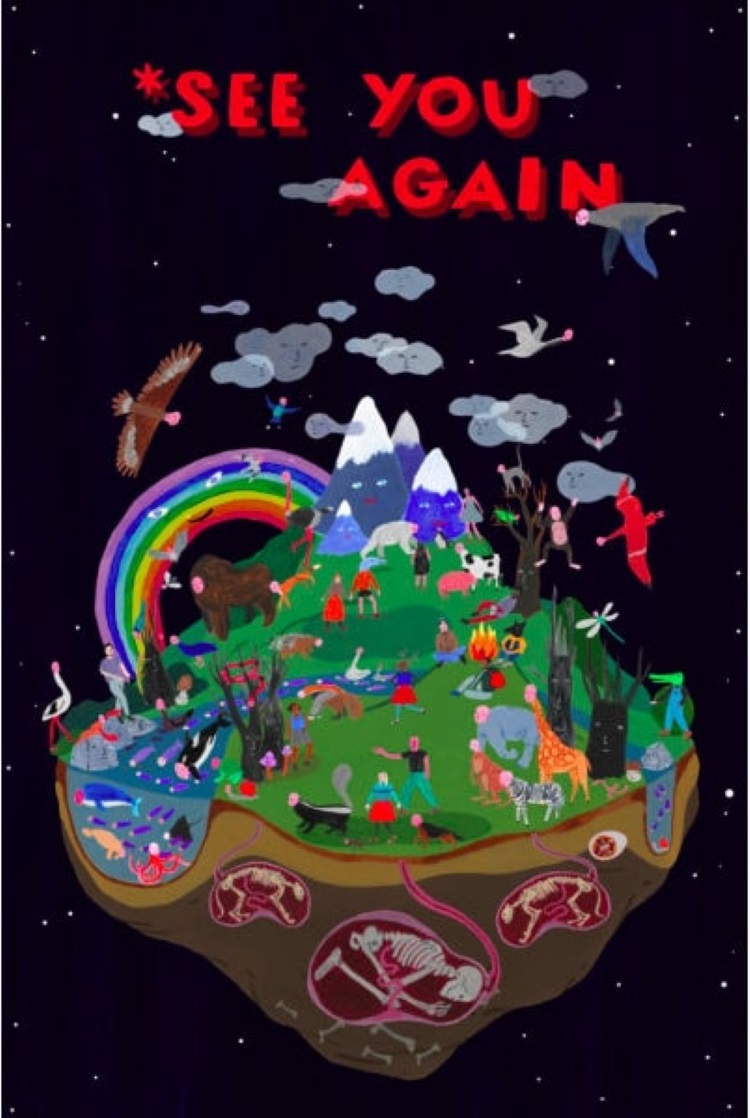

I stop at Stasele Jakunskaite’s *See You Again. An inkjet print of buried skeletons feeding the life on Earth’s surface. The bones lie crouched like foetuses in the dirt. And the threads leading from their womb-graves are joined to the mountains and beasts and trees and people who stand on the surface. The animals all have human faces, but some of the people are animal-headed like Egyptian deities. Jakunskaite writes in the exhibition’s catalogue that “The belief that the life of a human soul does not end with death is very old and common for many different cultures.”

Here this ancient thinking is seen through modernity’s lens. The childlike quality of the picture makes it almost seem alive – as if it were an animation rather than a still. The Earth in the image is no more than a dirt clod among stars. A microcosm of our own planet. But through its simplicity Jakunskaite’s work makes the link between humanity and the Earth clear as a winter sky. Where, in reality, it can get lost in the cracks between religions and sciences and mythologies.

All beliefs spring from mankind. That may sound like a truism, but it is our ability to wonder that built the bridges that link Christ, Valhalla, the Milky Way, and Earth. We stand at the nexus of all these ways. Where Gods meet land and oceans, and logic melds into magic. *See You Again highlights this link between dirt, body, and soul. Humanity came from the Earth and will disappear back into it. Only for more of us to appear and build upon our aeons of knowledge and wisdom. Feeding the soul through our senses.

Creation is an act that combines the physical with the spiritual and intellectual. Out of the hinterland between the soul and mind comes the work. A physical thing that months before was just an idea, as nebulous as any thought. I walk into the next room and stop before Micky Donnelly’s Landscape With Donkey’s Feet (Henry’s Dream). A wide painting that takes up its own stretch of wall. Just as the living grow from the Earth in *See You Again, Donnelly’s painting began with a painting by Paul Henry, called Dawn, Killary Harbour. In the catalogue, Donnelly writes that Henry’s painting “encapsulates the mythologised and romantic view of the West of Ireland”. From this wellspring came something new. Out of the past comes the present. And so on until we are eventually stopped.

The stairs to the bottom floor are behind Landscape With Donkey’s Feet (Henry’s Dream). I turn the corner and look up at the back of its wall. Where visitors have hung their own sketches of the paintings that make up Untitled [Landscape]. I stop for a minute and see that Donnelly’s was the most-reproduced work of the lot. I smile as I walk down the stairs, towards the tall windows that look out on the Shannon. The winding, black brushstroke that colours the Luan Gallery’s glass.